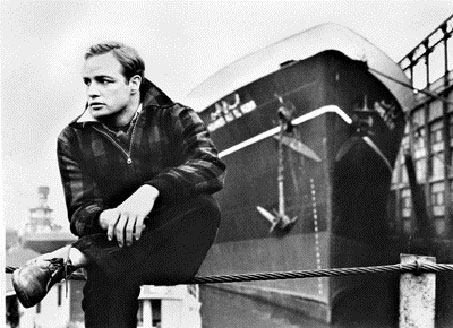

On the Waterfront

A former prizefighter (Marlon Brando) is caught up in a corrupt union

headed by a mobster (Lee J. Cobb), but starts to question his beliefs

when he falls for the sister (Eva Marie Saint) of a man who was murdered

for informing.

Kazan's boldly emphatic style was never put to better use than in

this gritty social drama, which captured the Oscars for picture,

director and actor. The atmosphere of menace which had hitherto been

confined to the crime picture (later known as "film noir") was here

skillfully expanded to a wider realm, and combined with a visual style

that emphasizes the desolation of the urban landscape and the cramped

inner life of the working class. It was something new in American

pictures, the product of a decade-long shift away from studio to

location shooting, and from the old "seamless" technique to a

rough-edged style influenced by the school of method acting. If in some

ways it seems old hat today, part of that is due to its immense

influence on later productions. Kazan's boldly emphatic style was never put to better use than in

this gritty social drama, which captured the Oscars for picture,

director and actor. The atmosphere of menace which had hitherto been

confined to the crime picture (later known as "film noir") was here

skillfully expanded to a wider realm, and combined with a visual style

that emphasizes the desolation of the urban landscape and the cramped

inner life of the working class. It was something new in American

pictures, the product of a decade-long shift away from studio to

location shooting, and from the old "seamless" technique to a

rough-edged style influenced by the school of method acting. If in some

ways it seems old hat today, part of that is due to its immense

influence on later productions.

For all its starkness and sense of alienation, On the Waterfront

still suffers from a simplistic story and script, and an overwrought

dramatic emphasis. It's safe to say that the film probably woudn't have

worked at all but for the great lead performance of Brando. His Terry

Malloy - brutal, ignorant, mutely suffering, constantly wavering between

tenderness and aggression - is a fully realized dramatic creation that

demonstrates just why he was the most admired actor of his time. Watch

him, not only in the great scene with Rod Steiger (as his brother) in

the taxicab, but also in his scene at the bar with Saint, or on the

rooftop with the young toughs, or in just about any of his scenes - and

marvel at the way his inflections, hesitations, body movements,

everything about him, displays an inner conviction and power that makes

his character exist in the flesh. He carries the film on his shoulders

and makes it work.

Most of the other actors do fine, particularly Cobb, who is his usual

larger-than-life self. The one glaring exception is Karl Malden -

unconvincing in the admittedly misconceived role of a crusading priest.

Leonard Bernstein's music is great on its own terms, but too

overpowering at times as a film score. And the ending - well, it's

dramatic, alright, but if you think anything like that would really

happen outside of a movie, you haven't seen too much of the world.

It's hard to watch the film without relating it to Kazan's own

controversial decision, two years before, to turn on his friends and

"name names" to HUAC during the witch hunts. There is something awfully

defensive and self-serving about the aspect of the film which treats of

informing as a moral act. Seen without reference to the director's

history, however, it doesn't create the impression of a reactionary

tract, but rather an impassioned drama about the moral awakening of an

unlikely hero. The film's crude theatricality has not worn well over

time, but the visual style, and especially the central performance by

Brando, insures that it has a place in the pantheon of classic films.

|